Fay Mackey elected as Trustee Emerita at the MFA

The 2021-2022 MFA Board of Trustees has elected Fay Mackey as Trustee Emerita

The 2021-2022 MFA Board of Trustees has elected Fay Mackey as Trustee Emerita, an honorary lifetime position and looks forward to her continued involvement, sharing her insights on a museum she loves and introducing new trustees to this exceptional institution. The Museum of Fine Arts will continue to benefit from Fay’s knowledge, commitment, and perhaps most of all, her heart and spirit.

Fay grew up at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg. Her great-aunt Margaret Acheson Stuart founded the MFA, the city’s first art museum. Mrs. Stuart asked her nephew and Fay’s father, Charles W. Mackey, to serve on the first Board of Trustees and elected him as Vice President. He continued his leadership role as Board Chairman and later as President for 10 years. When he retired, the Board named him President Emeritus.

Mr. Mackey is one of the most impressive figures in the Museum’s history. He almost single-handedly raised the funds to double the galleries from 10 to 20 and to add a second floor for administrative offices, a classroom, and a library by 1989. He initiated the Challenge Fund, now Annual Giving, and always provided a substantial lead gift. He was also a major sponsor of numerous exhibitions.

One of the Museum’s largest galleries is named in honor of Fay’s paternal grandfather, Cyrus Fay Mackey. Funds for its construction were provided by Fay’s grandmother.

When Fay returned to St. Petersburg in 1998, she took up the family mantle. The MFA has never been just a museum for Fay. It is truly part of her DNA. She began as a trustee in 1999, alternating on and off the Board over the years. She served on the accessions and membership committees and chaired the education committee. She was selected to chair the Museum’s 50th Anniversary Celebration in 2015.

Fay has also been a very active member of The Margaret Acheson Stuart Society, assisting with many fundraisers. She co-chaired the Fashion Show in 2010 with Dr. Dimity Carlson, the current Chair of the Board of Trustees.

As a Museum trustee, Fay has always believed it was important to keep the rich traditions of the MFA alive as the institution has moved forward. She has a perspective that spans the history of the institution, beginning with childhood memories. Rarely has one family played such an important role in the development of an American art museum. Board members look forward to working with Fay for years to come.

Civil Rights Movement Photo Collection: Selma, Alabama (1965)

July 13, 2020 | Dr. Allison Moore, Curator of Photography

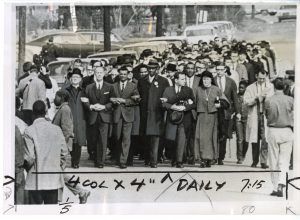

This photograph, taken on March 15, 1965 by the United Press International (UPI), shows a row of Civil Rights clergy leading demonstrators and mourners to the Rev. James Reeb’s funeral in Selma, Alabama. The hand-drawn black line shows a typical editorial mark-up denoting the margin of street that was cropped out of the published photo when it appeared in newspapers like the San Francisco Examiner. We surmise that the tall man in the center wearing a fedora hat is Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, a leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which he co-founded with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others. The Black man next to him with the moustache and striped tie is the late Rev. C. T. Vivian, who passed away July 17, 2020 at the age of 95. Vivian, considered King’s “lieutenant,” was one of the major architects and leaders of the marches and protests of the Civil Rights Movement. This photograph reminds us of the long process of protest and sacrifice that eventually resulted in the Civil Rights Voting Act.

On March 7, 1965, along with 70 million Americans, Reeb had seen television footage of “Bloody Sunday,” a peaceful protest for voting rights in Selma violently turned back from the Edmund Pettus Bridge by police wielding bullwhips, billy clubs and tear gas. Seventeen protesters were hospitalized and more than 50 injured — including a very young John Lewis, a pillar of the Civil Rights Movement and longtime Georgia Congressman. (Lewis died July 17, 2020, on the same day as Vivian.) On Bloody Sunday, a 14-year-old girl, Lynda Blackmon, was severely beaten, and the march’s local organizer, Amelia Boynton, was knocked unconscious. King sent out a call to clergy to support the protests and Reeb, a 38-year-old Boston minister with young children, traveled to Selma to answer the call.

On March 9, Reeb walked in a symbolic protest led by King that stopped at the bridge to pray, and then turned around. That evening, Reeb and two other white men were badly beaten by the Ku Klux Klan. Two days later, Reeb died from brain injuries. King delivered the eulogy at Reeb’s funeral, saying that he “symbolizes the forces of goodwill in our nation. He demonstrated the conscience of the nation. He was an attorney for the defense of the innocent in the court of world opinion. He was a witness to the truth that men of different races and classes might live, eat, and work together as brothers” (March 15, 1965).

Reeb’s was the second death in Alabama in the protest spring of 1965. On February 18, during a protest for voting rights in nearby Marion, Alabama, a 26-year-old Black deacon named Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot in the stomach while protecting his mother from a violent white police officer. Jackson died several days later. As the recent murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis by police officers spurred the current Black Lives Matter protests, so the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson galvanized Civil Rights organizations, and spurred the protest on March 7, a day that became known as “Bloody Sunday.” Yet Jackson’s death went unremarked nationally. While Reeb’s murder aroused needed national attention for voting rights in Selma, it also created tension in the Movement because of the disparity of notice paid to Jackson’s murder.

The Civil Rights focus on Selma had begun in January 1965, when King met with leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and local organizers to solve the problem of voting rights. While the Civil Rights Act had been passed in 1964, Black voter registration was still low across the southern states. Statistics were worst in Dallas County, Alabama, where fewer than 2 percent of Blacks were registered to vote, despite accounting for 57 percent of the overall population. Intimidation and threats, both economic and physical, by the state and the Ku Klux Klan alike, kept Black people from registering to vote. On February 1, King led protesters to register to vote at the Dallas County Courthouse, where he and others were arrested. King refused to post bail, calling national attention to Selma, and further protests ensued.

In response to the deaths of Reeb and Jackson and the earlier protests, on March 15, the day of Reeb’s funeral, newly-elected President Lyndon B. Johnson called on Congress to establish the Civil Rights Voting Act. Johnson praised the efforts of Civil Rights protesters against the punishing, racist views of Alabama Governor George Wallace. In this speech Johnson repeated the iconic Civil Rights slogan, “We shall overcome.” A week later, Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard —a remarkable act of presidential support against state aggression—to protect one of the most memorable and successful Civil Rights protests: the 54-mile march from Selma to Montgomery. Led by King, it began on March 21 with over 3,000 people, and ended five days later at the Alabama State Capitol courthouse with 25,000 protesters, including numerous celebrities. The Civil Rights Voting Act was signed into law by Johnson later that year, in August 1965.

Image credit: Marching Six Abreast, Selma Demonstrators were Stopped at Selma Wall, United Press International (American), 1965, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Ludmila and Bruce Dandrew from The Ludmila Dandrew and Chitranee Drapkin Collection

Conserving the Collection – A Medici Pietre Dure panel

July 1, 2020

Erin Wilson, Curatorial and Registration Assistant

One of the most exciting aspects of working in a museum is the chance to make new discoveries. This spectacular pietre dure, or hard stone, panel depicting a vase filled with brightly colored flowers (Figure 1) has a fascinating history. In 1964, it came to the Museum as part of a larger gift of furniture and decorative arts. The panel had been mounted onto an iron base, and functioned as a decorative table (Figure 2). For decades, it was thought to be a nineteenth-century historicist work. Not surprising, as much decorative art and design during this period was derivative of an earlier aesthetic. However, in 2007, visiting scholars made a stunning revelation—our nineteenth century table was, in fact, a long-lost work commissioned by the Medici family in the early 1600s.1

Figure 1.

Figure 2. Close up of iron base utilized to turn this wall panel into a table.

The Museum’s hard stone panel was one of a series that once decorated the walls of a small chapel in the Villa del Poggio Imperiale, a Medici palace outside of Florence. Records indicate that floral designs, such as the MFA’s, would have been interspersed with complementary panels depicting blossoming orange trees (Figure 3). In the last decades of the eighteenth century, the villa was renovated in the Neoclassical style, and the inlaid stone panels were removed. While the original number produced is unknown, a 1789 inventory, found in the archives of the Galleria dei Lavori, lists eleven panels from this suite. These were dispersed and sold in the last half of the nineteenth century.2 Currently, only six are known to still exist—one is in the collection of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, two belong to the Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure, two are in the Victoria & Albert Museum collection, and lastly, ours—the most recent to be discovered.

Figure 3: Panel depicting a blossoming orange tree, on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2018. The V&A holds the only known example of this design.

Pietre dure is a highly-detailed, complex inlay process in which a skilled artist uses thin slices of marble and semi-precious stones to form a composition. Similar to marquetry in woodworking, pietre dure is often used to embellish furniture and other decorative objects. While the process loosely has origins in antiquity,3 it was popularized in Florence with the establishment of the Galleria dei Lavori (later renamed the Opificio delle Pietre Dure) by Grand Duke Ferdinand I de’Medici in 1588. The background of the MFA’s panel is composed of black Belgian marble. According to Annamaria Giusti, former Director of the Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure, such panels are among the first examples of black marble being utilized as a ground for Florentine mosaics.4 This dark surface gives the stones that comprise the design, including agate, jasper, verde antico marble, and Lapis Lazuli, an incredible richness and lustre. Pietre dure was highly fashionable in the seventeenth and eighteenth-centuries and numerous exquisite examples exist— many depicting floral still lifes, such as the one belonging to the MFA.

Although objects of pietre dure appear durable, they are in fact quite delicate. There is no documentation regarding the condition of the panel when it came to the Museum in 1964, so it is difficult to know if it degraded in the last fifty years. However, there are various issues that currently make displaying it impossible, including cracked, loose, and missing stones (Figure 4). Thanks to the generosity of the Collectors Circle, a support group that raises funds for significant acquisitions for the MFA, we are finally able to conserve this spectacular panel, allowing visitors to once more view it as originally intended.

Figure 4. Detail of PRE-CONSERVATION condition.

RLA Conservation, Inc., based in Miami and Los Angeles, was contracted to take on this important task. Recently, RLA conserved the Museum’s set of Antioch mosaics, and we are thrilled to be working with them once again. Conservation goals for this project include removing the iron table legs, which are not original and likely added around 1900, carefully cleaning decades-old grime from the surface, and repairing loose and damaged stonework.

Progress is already well underway; check back for updates!

1 Koeppe, Wolfram, ed. Art of the Royal Court. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008. Exhibition catalogue. The MFA’s panel is noted as belonging to this suite of works on page 179.

2 Koeppe, Wolfram, ed. Art of the Royal Court. 178-179.

3 Koeppe, Wolfram, Mysterious and Prized: Hardstones in Human History before the Renaissance,” in Art of the Royal Court, ed. Wolfram Koeppe, 3-11. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

4 Koeppe, Wolfram, ed. Art of the Royal Court. 178-179. See description regarding similar panel in the Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure collection, pg. 179.