Civil Rights Movement Photo Collection: Selma, Alabama (1965)

July 13, 2020 | Dr. Allison Moore, Curator of Photography

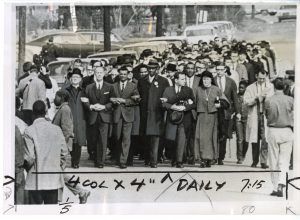

This photograph, taken on March 15, 1965 by the United Press International (UPI), shows a row of Civil Rights clergy leading demonstrators and mourners to the Rev. James Reeb’s funeral in Selma, Alabama. The hand-drawn black line shows a typical editorial mark-up denoting the margin of street that was cropped out of the published photo when it appeared in newspapers like the San Francisco Examiner. We surmise that the tall man in the center wearing a fedora hat is Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, a leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which he co-founded with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others. The Black man next to him with the moustache and striped tie is the late Rev. C. T. Vivian, who passed away July 17, 2020 at the age of 95. Vivian, considered King’s “lieutenant,” was one of the major architects and leaders of the marches and protests of the Civil Rights Movement. This photograph reminds us of the long process of protest and sacrifice that eventually resulted in the Civil Rights Voting Act.

On March 7, 1965, along with 70 million Americans, Reeb had seen television footage of “Bloody Sunday,” a peaceful protest for voting rights in Selma violently turned back from the Edmund Pettus Bridge by police wielding bullwhips, billy clubs and tear gas. Seventeen protesters were hospitalized and more than 50 injured — including a very young John Lewis, a pillar of the Civil Rights Movement and longtime Georgia Congressman. (Lewis died July 17, 2020, on the same day as Vivian.) On Bloody Sunday, a 14-year-old girl, Lynda Blackmon, was severely beaten, and the march’s local organizer, Amelia Boynton, was knocked unconscious. King sent out a call to clergy to support the protests and Reeb, a 38-year-old Boston minister with young children, traveled to Selma to answer the call.

On March 9, Reeb walked in a symbolic protest led by King that stopped at the bridge to pray, and then turned around. That evening, Reeb and two other white men were badly beaten by the Ku Klux Klan. Two days later, Reeb died from brain injuries. King delivered the eulogy at Reeb’s funeral, saying that he “symbolizes the forces of goodwill in our nation. He demonstrated the conscience of the nation. He was an attorney for the defense of the innocent in the court of world opinion. He was a witness to the truth that men of different races and classes might live, eat, and work together as brothers” (March 15, 1965).

Reeb’s was the second death in Alabama in the protest spring of 1965. On February 18, during a protest for voting rights in nearby Marion, Alabama, a 26-year-old Black deacon named Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot in the stomach while protecting his mother from a violent white police officer. Jackson died several days later. As the recent murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis by police officers spurred the current Black Lives Matter protests, so the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson galvanized Civil Rights organizations, and spurred the protest on March 7, a day that became known as “Bloody Sunday.” Yet Jackson’s death went unremarked nationally. While Reeb’s murder aroused needed national attention for voting rights in Selma, it also created tension in the Movement because of the disparity of notice paid to Jackson’s murder.

The Civil Rights focus on Selma had begun in January 1965, when King met with leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and local organizers to solve the problem of voting rights. While the Civil Rights Act had been passed in 1964, Black voter registration was still low across the southern states. Statistics were worst in Dallas County, Alabama, where fewer than 2 percent of Blacks were registered to vote, despite accounting for 57 percent of the overall population. Intimidation and threats, both economic and physical, by the state and the Ku Klux Klan alike, kept Black people from registering to vote. On February 1, King led protesters to register to vote at the Dallas County Courthouse, where he and others were arrested. King refused to post bail, calling national attention to Selma, and further protests ensued.

In response to the deaths of Reeb and Jackson and the earlier protests, on March 15, the day of Reeb’s funeral, newly-elected President Lyndon B. Johnson called on Congress to establish the Civil Rights Voting Act. Johnson praised the efforts of Civil Rights protesters against the punishing, racist views of Alabama Governor George Wallace. In this speech Johnson repeated the iconic Civil Rights slogan, “We shall overcome.” A week later, Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard —a remarkable act of presidential support against state aggression—to protect one of the most memorable and successful Civil Rights protests: the 54-mile march from Selma to Montgomery. Led by King, it began on March 21 with over 3,000 people, and ended five days later at the Alabama State Capitol courthouse with 25,000 protesters, including numerous celebrities. The Civil Rights Voting Act was signed into law by Johnson later that year, in August 1965.

Image credit: Marching Six Abreast, Selma Demonstrators were Stopped at Selma Wall, United Press International (American), 1965, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Ludmila and Bruce Dandrew from The Ludmila Dandrew and Chitranee Drapkin Collection

« Conserving the Collection – A Medici Pietre Dure panel Fay Mackey elected as Trustee Emerita at the MFA »