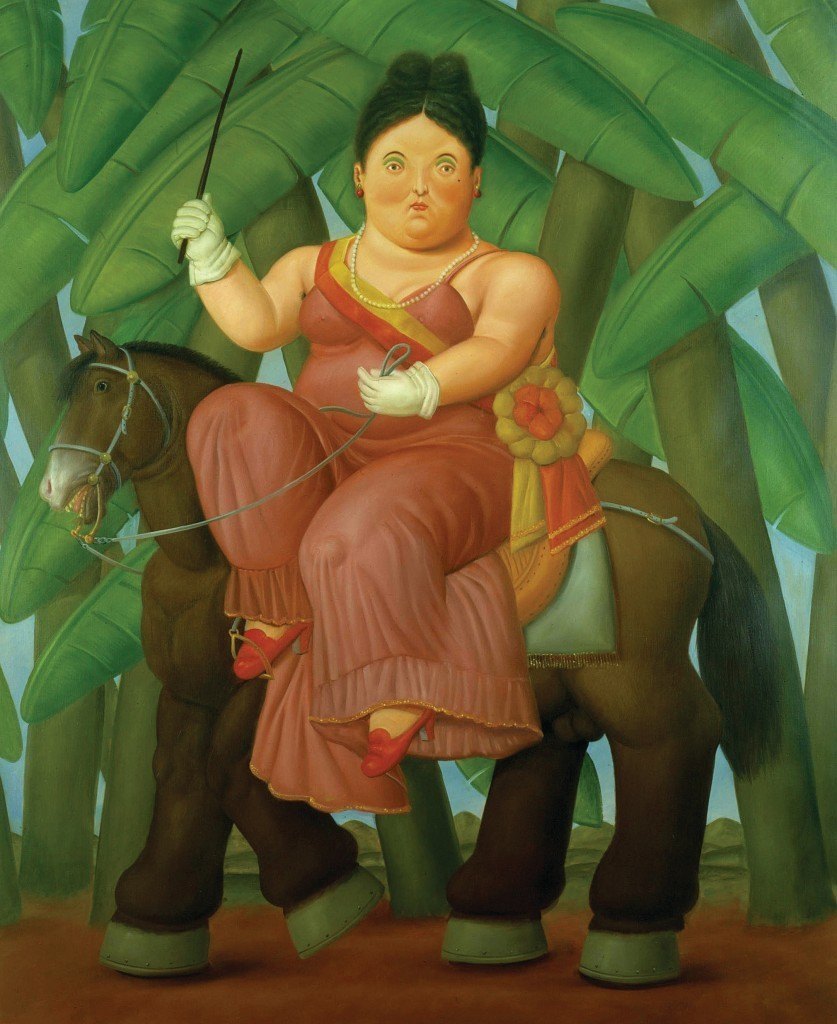

The Baroque World of Fernando Botero

January 9 through April 4, 2010

Botero is one of Colombia’s and the world’s most popular artists. His monumental bronzes have been seen on Park Avenue in New York, the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and the Champs Elysees in Paris. The Baroque World of Fernando Botero is the first time such a large exhibition of his work has been featured in the Tampa Bay area.

This is also the first retrospective of the artist’s work in North AMerica since the acclaimed 1979 survey at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. Spotlighting 100 stunning paintings, sculptures, and drawings, this new exhibition is drawn from Botero’s private collection. These are key works he saved or bought back, providing the artist’s personal look at the amazing sweep of his career.

Born in 1932 in Medellin, Colombia, Botero is a truly international artist, reflecting diverse influences. As a teenager, he was drawn to the work of Picasso and was expelled from his Catholic high school for writing an admiring essay on the modernist master. Later studies in Europe led to exposure to Velazquez (his portraits of Spanish royalty); Goya (Los desastres de la guerra); Durer (particularly his Adam and Eve); Rubens; Italian Renaissance fresco painters; and French artists Courbet, Ingres, and Delacroix. The Mexican muralists Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros and the great Frida Kahlo (her haunting self-portraits) have also influenced his work.

He sketched his breakthrough mandolin in 1956 in Mexico City. By making the central opening of the instrument very small, he enlarged the volume of the entire mandolin. According to exhibition curator Dr. John Sillevis, “It felt like a shock. From now on he knew what he was going to do. He would enlarge everything he would draw or paint to a baroque shape, an expression of sumptuousness and sensuality, not only in a human figure, but also in still life, in fruits, or in a mandolin.

The Museum exhibition contains a later, striking painting, Still Life with Mandolin (1998). The still life, in fact, has been critical to Botero’s work almost from the very beginning. Botero has explained: “When you see a still life of mine, you will notice that the knives and forks, the grit, the table, the napkins, everything is rendered in the same fashion, therefore the whole work radiates a sense of unity, harmony, and coherence. That is what communicates its essential truth.